Bitcoin Consumes More Energy Than a Lot of Countries. Why Is That Possible?

- By Kriss

- Published on: September 13, 2021

Cryptocurrencies have emerged as one of the world’s most attractive, yet mystifying, investments. They have skyrocketed in value. Crypto markets have crashed. Their supporters argue that they would revolutionize the globe by displacing established currencies such as the dollar, rupee, and ruble. They are even named after dog memes.

And cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, one of the most popular, consume enormous amounts of electricity just to exist.

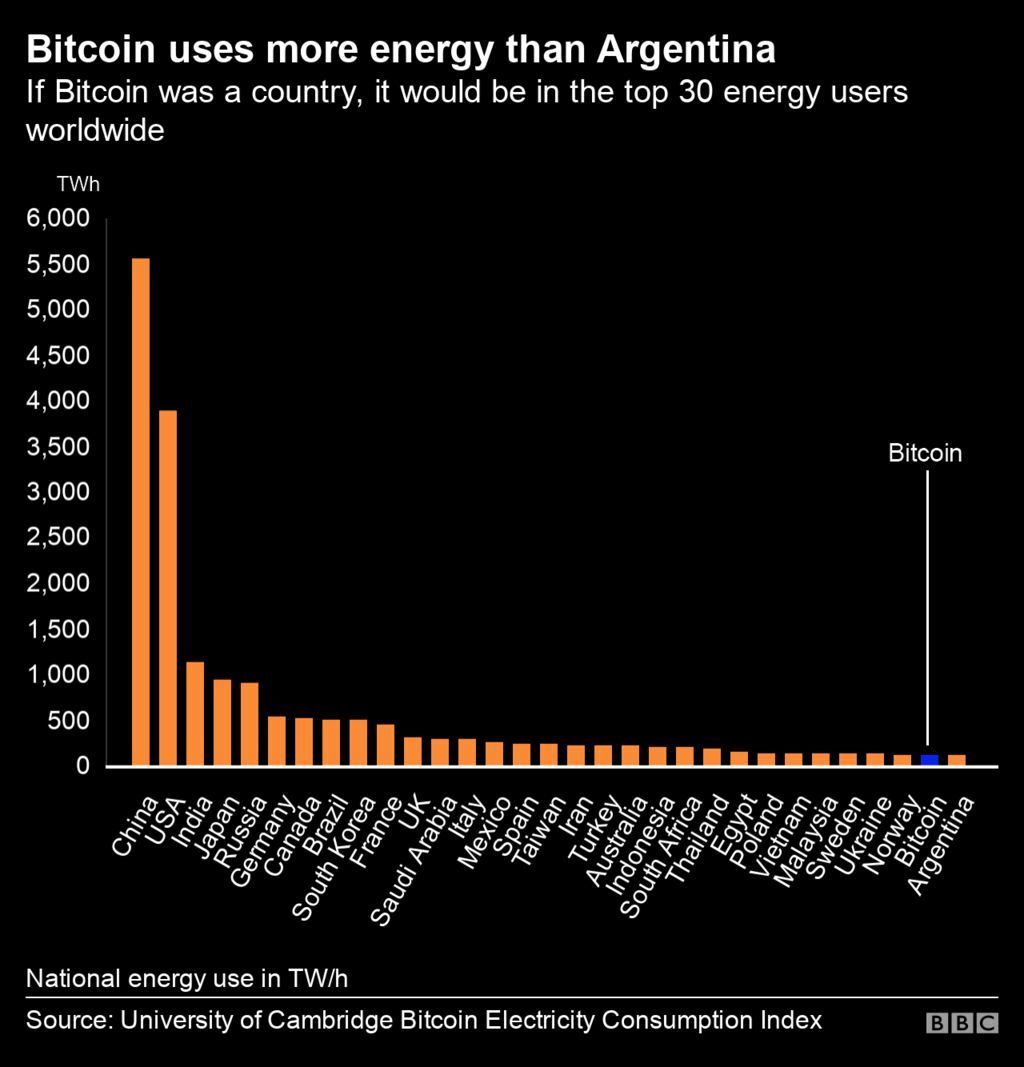

In a moment, we’ll explain how that works. But first, think about this: The act of producing Bitcoin to spend or trade uses roughly 91 terawatt-hours of electricity each year, which is more than Finland’s population of 5.5 million people or Argentina’s.

In only the last five years, that demand has surged tenfold, accounting for over half of all electricity consumed worldwide.

So, why is it so power-hungry?

Money has long been regarded to be something you can handle in your hand, such as a $1 bill. Currencies like this appear to be a simple yet smart concept. A government issues some paper and backs it up with a guarantee of its worth. Then we trade it for vehicles, candy bars, and tube socks between ourselves. We have the option of giving it to anyone we want or even destroying it. Things can get a lot more confusing on the internet.

Traditional forms of money, such as those issued by the US or other governments, aren’t completely free to be used however you want. Banks, credit-card networks, and other middlemen can regulate who can use their financial networks and what they can be used for – frequently for good reason, such as to prevent money laundering and other illicit activity. However, this might mean that if you send someone a large sum of money, your bank will disclose it to the authorities, even if the transaction is totally legal.

So a group of free thinkers — or anarchists, depending on who you ask — began to wonder: What if there was a way to get rid of these kinds of constraints?

In 2008, an anonymous person or persons using the moniker Satoshi Nakamoto proposed a cash-like electronic payment system that would do just that: eliminate the intermediaries. That is where Bitcoin got its start.

Because transactions would be managed by a decentralized network of Bitcoin users, users wouldn’t have to trust a third party — a bank, a government, or anything else, according to Nakamoto. In other words, it could not be controlled by a single person or entity. All Bitcoin transactions would be freely recorded on a public ledger accessible to anybody, and new Bitcoins would be minted as a reward for assisting in the management of this vast, computerized ledger. However, the total number of Bitcoins available will be limited. The idea was that as demand grew over time, Bitcoins would gain value.

This concept took some time to catch on. A single Bitcoin, on the other hand, is now worth roughly $50,000 (though this value may vary substantially by the time you read this), and no one can stop you from transmitting it to whomever you wish. (Of course, if someone is caught buying illegal drugs or orchestrating ransomware attacks, two of the many nefarious uses for which cryptocurrency has proven appealing, they will still be prosecuted.)

However, operating a digital currency of that worth without a central authority requires a significant amount of computational power.

1. It all starts with a transaction

You now have a “digital wallet” containing Bitcoin. To use it, simply deposit Bitcoin into the digital wallet of the person from whom you are purchasing something. It’s as simple as that.

However, the Bitcoin network must first validate that transaction, as well as any other Bitcoin exchange. In its most basic form, this is the method by which the seller can be certain that the Bitcoins he or she is receiving are genuine. This is the example of Proof of Work, find out how it differs from Proof of Stake.

This goes right to the heart of the Bitcoin accounting system: the upkeep of the massive Bitcoin public ledger. And it is here that the majority of the electrical energy is consumed.

2. And so begins the global guessing game

Companies and individuals known as Bitcoin miners compete for the right to validate transactions and enter them into the public ledger of all Bitcoin transactions all over the world. They essentially compete in a guessing game, using powerful and power-hungry computers to try to outwit the competition. Because if they succeed, they will be rewarded with newly created Bitcoin, which is, of course, extremely valuable.

The term “mining” refers to the competition for newly created Bitcoin.

You can compare it to a lottery or a dice game. Consider the following scenario: you’re at a casino, and everyone is playing with a 500-sided die. (It would have billions of billions of sides, but that’s difficult to draw.) The first person to roll a number less than ten wins.

The more computer processing power you have, the more quick guesses you can make. So, unlike in a casino, where you only have one die to roll at human speed, you may have a number of computers guessing at the same time.

The Bitcoin network is designed to make the guessing game increasingly difficult as more miners join in, emphasizing the importance of fast, power-hungry machines even more. It’s specifically designed so that winning a round always takes an average of 10 minutes. The game is re-calibrated to make it more challenging if more people join the dice game and start winning faster. Consider the following scenario: You must now roll a number that is less than 4 or a perfect 1.

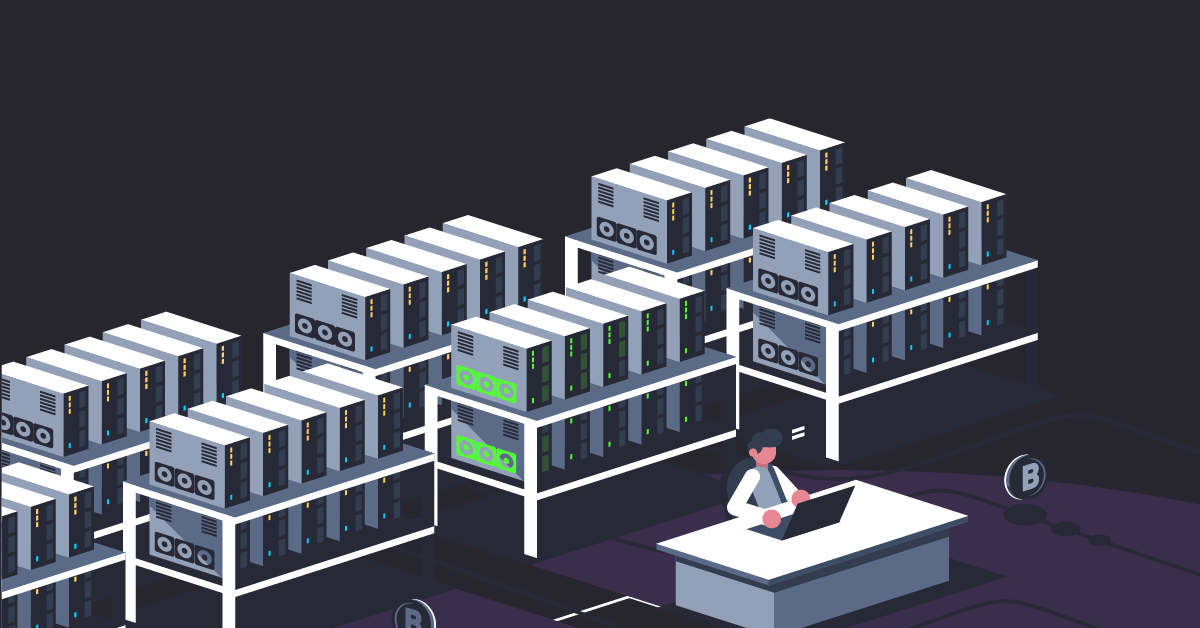

That’s why Bitcoin miners today have warehouses crammed with powerful computers, all racing at high speed to guess large numbers while consuming massive amounts of electricity.

3. The winner receives hundreds of thousands of dollars in new Bitcoin

The winner of the guessing game verifies a standard “block” of Bitcoin transactions and receives 6.25 newly created Bitcoins worth around $50,000 apiece. As a result, it’s easy to see why people might rush to mining.

Why is it necessary to play such a difficult and costly guessing game? This is due to the fact that simply recording the transactions in the ledger would be trivially simple. As a result, the problem is to ensure that only “trustworthy” computers perform this function.

A malicious actor might disrupt the system, preventing legitimate transfers or defrauding people with bogus Bitcoin transactions. However, because of the way Bitcoin is constructed, a bad actor would have to win the majority of guessing games in order to gain control of the network, which would take a lot of money and electricity.

In Nakamoto’s scheme, a hacker would be better off spending his or her time mining Bitcoin and collecting the rewards than attacking the system itself.

Bitcoin mining converts electricity into security in this way. It’s also why the system is designed to waste energy.

Bitcoin's ever-increasing energy consumption

Anyone with a computer could easily mine Bitcoin in its early days, when it was less popular and valued less. Not that much these days.

To keep the continually operating gear from overheating, you now need highly specialized machines, a lot of money, a lot of space, and enough cooling power. As a result, mining is now done in massive data centers owned by corporations or groups of people.

In fact, operations have consolidated to the point where only seven mining companies currently control nearly 80% of the network’s computational capacity. (The goal of “pooling” computer power in this way is to more equitably distribute profits, so members get $10 every day rather than $50,000 every ten years, for example.)

Mining takes place all over the world, often where there is a plentiful supply of inexpensive energy. Much of the Bitcoin mining has been done in China for years, but the country has recently begun to crack down. China’s proportion of worldwide Bitcoin mining fell to 46 percent in April from 75 percent in late 2019, according to researchers at the University of Cambridge who have been studying the industry. Meanwhile, the United States’ mining stake increased from 4% to 16% over the same time span.

Bitcoin mining entails more than just carbon dioxide emissions. Hardware accumulates as well. Everyone wants the newest, quickest machinery, which leads to rapid turnover and an increase in e-waste. According to Alex de Vries, a Paris-based economist, the computing capability of mining technology doubles every year and a half, rendering older machines obsolete.

By the beginning of 2021, Bitcoin alone has generated more e-waste than numerous midsize countries, according to his projections. Mr. de Vries, who runs Digiconomist, a site that studies the long-term viability of cryptocurrencies, said, “Bitcoin miners are entirely disregarding this issue since they don’t have a solution.” “These machines have been abandoned.”

Could Bitcoin be greener?

What if Bitcoin could be mined with more renewable energy sources, such as wind, solar, or hydropower?

Due to the structure of Bitcoin, which is a decentralized currency with primarily anonymous miners, determining how much of it is powered by renewables is difficult.

Bitcoin’s use of renewables is estimated to be somewhere between 40% and over 75% globally. However, using renewable energy to fuel Bitcoin mining means it won’t be available to power a home, a factory, or an electric car, according to experts.

A small number of mines are experimenting with capturing extra natural gas from oil and gas drilling sites, but such examples are few and difficult to measure. Furthermore, this approach may lead to more drilling in the future. The surplus hydropower generated during the rainy season in regions like southwest China has also been grabbed by miners. However, if those miners work during the dry season, they will mostly rely on fossil fuels.

According to Benjamin A. Jones, an assistant professor of economics at the University of New Mexico who researches the environmental impact of cryptomining, “baseload fossil fuels are still being used as far as we can tell.” He explained, “That’s why you get these radically divergent estimations.”

Is it possible to rewrite Bitcoin’s code to make it use less energy? Other minor cryptocurrencies have proposed an alternative bookkeeping system in which processing transactions is won by showing ownership of enough coins rather than computational labor. This is a more efficient method. However, it hasn’t been proven on a large scale, and it’s unlikely to catch on with Bitcoin since, among other things, Bitcoin investors have a strong financial incentive not to change, given how much they’ve already invested in mining.

Some governments, like environmentalists, are apprehensive of Bitcoin. They could theoretically alleviate the energy burden if they limited mining. But keep in mind that this is a network meant to function without the use of intermediaries. Mining limits are already in place in places like China, but miners are apparently shifting to coal-rich Kazakhstan and the low-cost but fragile Texas electric grid.

Bitcoin’s energy consumption will remain volatile for as long as its price does. Bitcoin mining does not require pickaxes or hard hats, yet it is also not a wholly digital abstraction: It is linked to the physical world of fossil fuels, electrical grids, and pollution, as well as the current climate problem. What started out as a forward-thinking digital money has already had real-world consequences, and they’re just getting worse.

- Share via

Kiara Sofia Smith

My current focus is blockchain technology and cryptocurrency. One could even call me a blockchain “enthusiast.” I have worked for almost a decade on several financial projects related to the stock market news, fundamental research and technical analysis for several blogs.

Recent Posts

Why There Might Be a Correlation Between U.S. Covid Cases and Crypto Prices

Why Should Google Create Their Own Blockchain and Cryptocurrency?

About Us

We are friendly cryptocurrency community and our mission is to give the latest info access to the people.